"Cinderella at 75: How a Princess and Glass Slippers Revived Disney"

In 1947, The Walt Disney Company faced a dire financial situation, being roughly $4 million in debt due to the commercial failures of Pinocchio, Fantasia, and Bambi, exacerbated by World War II and other factors. However, the release of the beloved princess tale, Cinderella, and her iconic glass slippers, played a pivotal role in saving Disney from potentially ending its animation story prematurely.

As Cinderella celebrates its 75th anniversary since its wide release on March 4, we spoke with several Disney insiders who continue to draw inspiration from this timeless rags-to-riches story. Interestingly, Cinderella's narrative parallels Walt Disney's own journey, offering not only hope to the company but also to a world in need of optimism and recovery post-war.

The Right Film at the Right Time --------------------------------To understand the significance of Cinderella, we must revisit Disney's fairy godmother moment in 1937 with Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. This film's unprecedented success enabled Disney to establish its Burbank studio and pursue further feature-length animated films.

Following Snow White, Disney's 1940 release, Pinocchio, despite its $2.6 million budget and critical acclaim, including Academy Awards for Best Original Score and Best Original Song, resulted in a $1 million loss. Fantasia and Bambi followed suit, underperforming and adding to the studio's debt. The primary reason was the outbreak of World War II, which disrupted Disney's European markets.

“Disney's European markets dried up during the war, and films like Pinocchio and Bambi couldn't be shown there, leading to poor performance,” explained Eric Goldberg, co-director of Pocahontas and lead animator on Aladdin’s Genie. “The studio then shifted to producing training and propaganda films for the U.S. government, and throughout the 1940s, Disney released Package Films like Make Mine Music, Fun and Fancy Free, and Melody Time. These were excellent, but lacked a cohesive narrative.”

Package Films, a series of short cartoons compiled into feature films, were Disney's strategy during this period. Between 1942’s Bambi and 1950’s Cinderella, six such films were produced, including Saludos Amigos and The Three Caballeros, which supported the U.S.’ Good Neighbor Policy against the spread of Nazism in South America. While these films helped manage costs and reduced Disney's debt from $4.2 million to $3 million by 1947, they hindered the studio's return to full-length animated features.

“I wanted to get back into the feature field,” Walt Disney reflected in 1956, as quoted in The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney by Michael Barrier. “But it required significant investment and time. A good cartoon feature demands a lot of both. My brother Roy and I had a heated discussion… It was one of my major upsets… I said we must either move forward, return to business, or consider liquidation or selling out.”

Facing the possibility of selling his shares and leaving the company, Walt, alongside Roy, decided to take a risk and focus on Cinderella, the first major animated feature since Bambi in 1942. The success of this film was crucial to the survival of Disney's animation studio.

“At that time, Alice in Wonderland, Peter Pan, and Cinderella were all in development, but Cinderella was chosen first due to its similarities to Snow White,” said Tori Cranner, Art Collections Manager at Walt Disney Animation Research Library. “Walt understood that post-war America needed hope and joy. While Pinocchio is a beautiful film, it lacks the joy that Cinderella brings. The world needed a story of rising from the ashes to something beautiful, and Cinderella was perfect for that moment.”

Cinderella and Disney’s Rags to Riches Tale

Walt Disney's connection to Cinderella dates back to 1922 when he created a Cinderella short at Laugh-O-Gram Studios, just before founding Disney with Roy. This short, based on Charles Perrault’s 1697 version of the tale, resonated with Walt due to its themes of good versus evil, true love, and dreams coming true.

“Snow White was a kind and simple girl who believed in wishing and waiting for her Prince Charming,” Walt Disney noted in Disney’s Cinderella: The Making of a Masterpiece special DVD feature. “Cinderella, however, was more practical. She believed in dreams but also in taking action. When Prince Charming didn’t come, she went to the palace to find him.”

Cinderella's character, resilient despite her hardships, mirrored Walt's own journey from humble beginnings through numerous failures to success driven by an unwavering dream and work ethic. Walt's early attempt to revive Cinderella as a Silly Symphony short in 1933 evolved into a feature film project by 1938, finally premiering over a decade later due to the war and other challenges.

Disney's ability to transform classic fairytales into universally appealing stories was key to Cinderella's success. “Disney took these age-old tales and infused them with his unique touch, making them more engaging and timeless,” Goldberg explained. “The original tales were often grim, serving as cautionary stories. Disney made them enjoyable for all audiences, modernizing them in the process.”

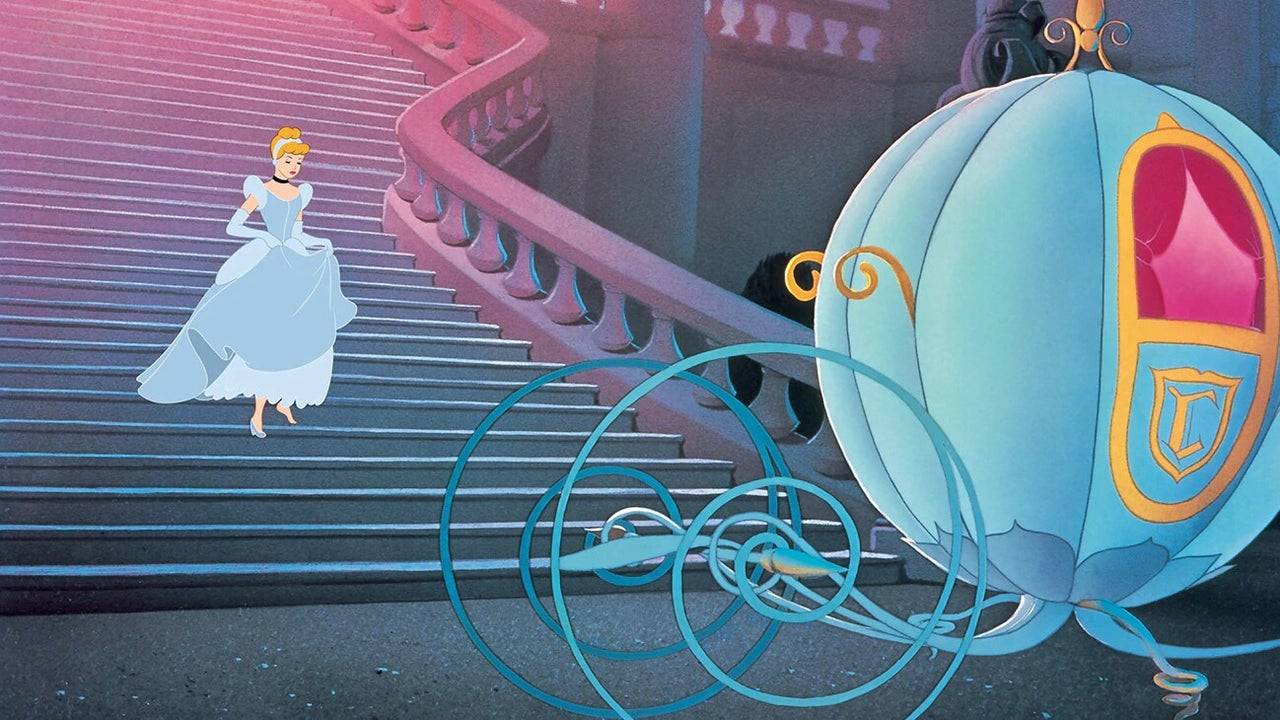

Cinderella's animal friends, including Jaq, Gus, and the birds, provided comic relief and allowed deeper insight into her character. The Fairy Godmother, reimagined as a bumbling, grandmotherly figure by animator Milt Kahl, added relatability and charm. The iconic transformation scene, where Cinderella's belief in herself manifests into a life-changing night, remains a highlight, with the dress transformation often cited as Walt's favorite animation sequence, crafted by Disney Legends Marc Davis and George Rowley.

Thanks so much for all your questions about Cinderella! Before we sign off, enjoy this pencil test footage of original animation drawings of the transformation scene, animated by Marc Davis and George Rowley. Thanks for joining us! #AskDisneyAnimation pic.twitter.com/2LquCBHX6F

— Disney Animation (@DisneyAnimation) February 15, 2020

“Every sparkle in that scene was hand-drawn and painted, which is incredible,” Cranner remarked. “There's a moment during the transformation where the magic pauses for a fraction of a second before completing, adding to its magic. It's like holding your breath before the release.”

The addition of the glass slipper breaking at the end of the film, a Disney innovation, underscores Cinderella's agency and strength. “Cinderella isn't just a passive character; she's strong and resourceful,” Goldberg noted. “When the slipper breaks, she presents the other one she's kept, showing her control and resilience.”

Cinderella premiered in Boston on February 15, 1950, and had its wide release on March 4, earning $7 million on a $2.2 million budget, becoming the sixth-highest grossing film of 1950 and receiving three Academy Award nominations. “Cinderella's success signaled Disney's return to narrative features, revitalizing the studio,” Goldberg said. “It paved the way for films like Peter Pan, Lady and the Tramp, Sleeping Beauty, 101 Dalmatians, and The Jungle Book.”

75 Years Later, Cinderella’s Magic Lives On

Today, Cinderella's influence remains strong, evident in Disney parks and modern films. Her castle inspires the iconic Disney castle logo, and her legacy is seen in scenes like Elsa’s dress transformation in Frozen, animated by Becky Bresee, which pays homage to Cinderella's magic.

The contributions of the Nine Old Men and Mary Blair to Cinderella's distinctive style and character are noteworthy. As Eric Goldberg concludes, “Cinderella's message of hope and perseverance resonates deeply. It shows that dreams can come true, no matter the era.”

-

Genshin Impact is set to launch its Version 5.4 update on February 12th, titled 'Moonlight Amidst Dreams.' This update introduces the Mikawa Flower Festival, a centuries-old celebration where humans and youkai unite to revel in life and lore.Where There Is Moonlight Amidst Dreams…The Mikawa festivalAuthor : Mia Apr 07,2025

-

Dive into the thrilling world of *CHASERS: No Gacha Hack & Slash*, where every battle is a real-time, action-packed adventure without the frustration of gacha mechanics. This game introduces you to a vibrant cast of characters known as "Chasers," each boasting unique skills and abilities that can tuAuthor : Adam Apr 07,2025

-

Car Games: Monster Truck StuntDownload

Car Games: Monster Truck StuntDownload -

Furby BOOMDownload

Furby BOOMDownload -

Jigsaw Puzzles Crown: HD GamesDownload

Jigsaw Puzzles Crown: HD GamesDownload -

Combat Car RiderDownload

Combat Car RiderDownload -

Real Moto RiderDownload

Real Moto RiderDownload -

Rhythm Racer: Phonk Drift 3dDownload

Rhythm Racer: Phonk Drift 3dDownload -

All Cars CrashDownload

All Cars CrashDownload -

Brasil Tuning 2Download

Brasil Tuning 2Download -

Drift Legends 2 Car RacingDownload

Drift Legends 2 Car RacingDownload -

Motorcycle Real SimulatorDownload

Motorcycle Real SimulatorDownload

- Hitman Devs' "Project Fantasy" Hopes to Redefine Online RPGs

- The Elder Scrolls: Castles Now Available on Mobile

- Minecraft's 'In Your World' Mod: A Chilling Update

- Resident Evil Creator Wants Cult Classic, Killer7, to Get a Sequel By Suda51

- Deadlock Characters | New Heroes, Skills, Weapons, and Story

- Fortnite Update: Mysterious Mythic Item Teased in Latest Leak

![[777Real]スマスロモンキーターンⅤ](https://images.0516f.com/uploads/70/17347837276766b2efc9dbb.webp)